David came to live with the Murches in 1959. A country boy from Temora, son of author Eric Schlunke, David had commenced but became disillusioned with a Degree at the University of New England in Armidale, NSW. Arthur was pleased to have David come on board as a pupil and assistant. Murch won a commission for a large mural for the Overseas Terminal at Circular Quay – the Foundation of European Settlement. Helga Lanzendorfer and Julian Halls were also engaged as pupils/assistants for the mural job.

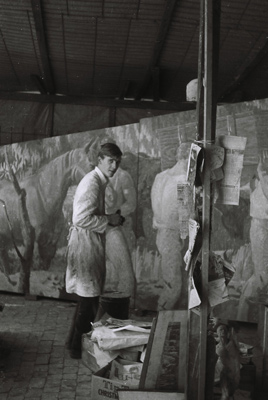

David Schlunke and Helga Lanzendorfer working on the mural 1962

David Schlunke and Helga Lanzendorfer working on the mural 1962

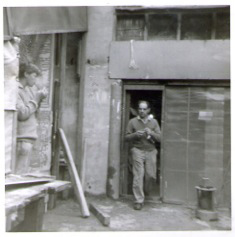

David Schlunke and Murch 1962 – photo by Julian Halls

David Schlunke and Murch 1962 – photo by Julian Halls

David has provided detailed information about working with Murch:

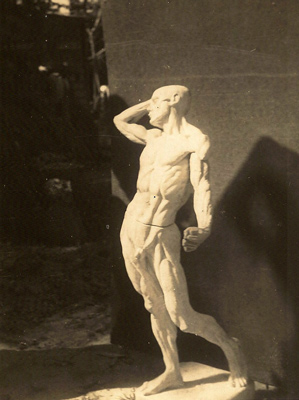

The Anatomical Man or St Bartholomew

David recalls:

Arthur always had an anatomical figure a bit less than 3ft tall. Anatomical figures are statues without their skin, giving a better view of the underlying muscle structure. He carried this figure to some of his night classes. He called it St Bartholomew but didn’t explain why for some time (A Christian martyr who was flayed alive; and is sometimes depicted in paintings carrying his skin folded over his arm).

Then came the big one who stood about 4 ft tall. Maybe Arthur got it from an art school which was purging itself of fuddyduddy plaster casts.

He was very keen to propagate from it. (To defy the iconoclasts) We decided it had to be done in two halves and so we cut it across at the waist; a very irksome act, and made a plaster spigot above and a recess below to help reassemble it. Oh yes, and we removed his extended arm to cast separately.

He decided to use jelly moulds rather than the fiddly business with plaster piece moulds. For complicated in-the-round jobs jelly is the preferred method, said Arthur; though I suspect he really wanted a pretext to teach us how to do jelly moulds.

The process which Arthur taught us (Helga and me) is fascinating and unforgettable.I had to buy the gelatine at Nock and Kirbys (“glue pearls”)

Basically the jelly, which is made from the glue pearls has to be a bit stiffer (less water) than the jelly one eats as a dessert. It is flexible and so can go around corners, though to a limited extent. Because the jelly moulds are floppsy they have to be encased on the outside by two sturdy plaster moulds: the “mother moulds”.

In order to make this setup we had to cover the original statue with clay about 14mm thick and then make the two plaster moulds over this clay. These mother moulds when set, were opened and the clay taken out and the original cleaned up. This left a hollow space between the mother mould and the original. This was then filled with molten jelly and left to set. (Parting agents were applied where appropriate). A clever system of “dimples and pimples” located the moulds together and the jelly sleeve inside the mothers.

Allow to cool.

So after opening the mother moulds and slitting the gelatine along the parting line; peeling oh so gently, the jelly off the original we were able to reassemble the jelly inside the mother moulds; with emptiness where the original anatomical figure had been.

So far this sounds easy. But wait.

I will start with the below-waist half.Plaster casts need armatures to hold them together during the rigors of birth and life. I made armatures out of 6mm iron rod; one down each leg and wired together in the base and top.We have to keep the armature from coming to the surface, so I had to make little plaster pads in the mould where the rods need support, and press the armature gently into the setting plaster.

I stress that this anatomical figure was a man.

The only place where I could make a plaster pad that would not pop out of its position when reassembling the moulds was the male genitalia. This cluster “dovetailed” itself in place nicely in the mould and supported the iron rods. A little known quality of male genitalia.

We used peanut oil as a parting agent inside the jelly mould. Everything assembled, and roped up and the whole mould inverted so plaster could be poured from the open part of the mould: the plinth.Then came the difficult part. As plaster sets it heats up. When jelly heats up it melts.

There are only a few minutes to get the business apart, get the jelly off the still-soft-and-warming-up plaster; put the plaster somewhere safe to set in peace, and rush the jelly molds up to put them in Ria’s refrigerator. Those of us who remember Arthur can imagine him indulging in his “frantic stress” state at this stage. As soon as I could I did the casting by myself to deprive Arthur of his stress.

We got about five casts done of the bottom half which was as many as we “needed” but the jelly, although getting mouldy and a bit torn here and there seemed OK so I took it upon myself to keep popping them out until the bitter end, and I got another five or so.

The top half, lacking long legs, was easier. I put plaster pads to support the armature in the face and elbow.

Because it was easier we did the top first and stopped at about five. When I went back to do another five to match the extra bottoms the jelly had decomposed into something imponderable, so we had some spare legs; which was a source of amusement for Ria and her visitors.

David Schlunke, Big Bush 2015

When asked further about casting and moulding techniques, David writes in April 2016:

I can remember Arthur’s backyard “kilns” or more likely drying ovens.

When he had bronze heads cast he insisted (understandably, because its fun, and probably nobody else would do it his way) on making the moulds and then melting out the wax, and then raising the temperature of the mould (Plaster of Paris and crushed brick and fired ceramic materials: tiles, plates etc) to as high a temperature as he could get in a backyard firebox; about that of molten lead I suppose, in order to generate and release whatever gases would be generated by the heat of the molten bronze when its poured in the foundry. If gases are generated in the bronze pouring there could be blow-holes, or the whole thing would explode. So he would keep his fire going for maybe a week. If it rained he would cover it and wait… Lots of wood came down from the “reserve”[Angophora Reserve] for the project.

We never did any bronze pours. It requires a pretty sophisticated furnace to get those temperatures.

We got our stuff done by a Mr Bob Ryan of Sophia St Surry Hills.

I still have the lead patterns and some bronze and one aluminium animals. They were all done in sand boxes. Solid cast; two sided.

David Schlunke made many small bronze pieces.

David shot this film of his studio and the very industrial-looking backyard of the Murch home in Avalon.

Avalon Backyard 1960s